26 April, 2018

Marino Lejarreta: the reed against the mountain

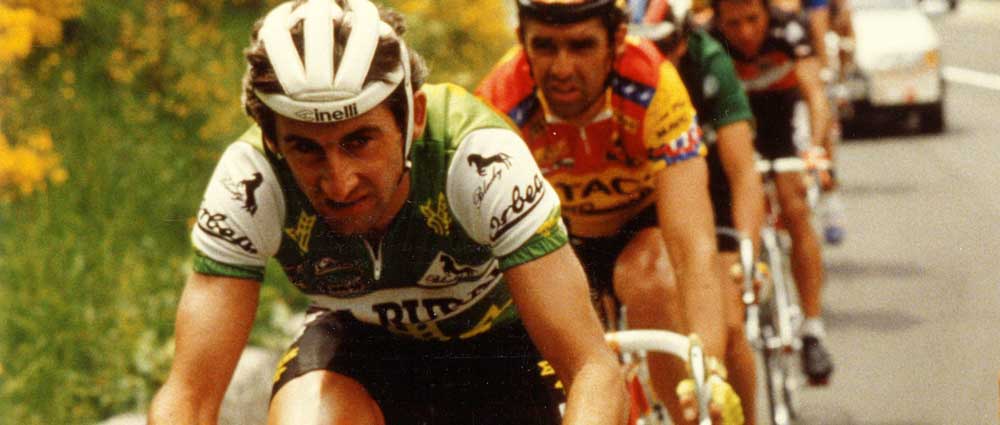

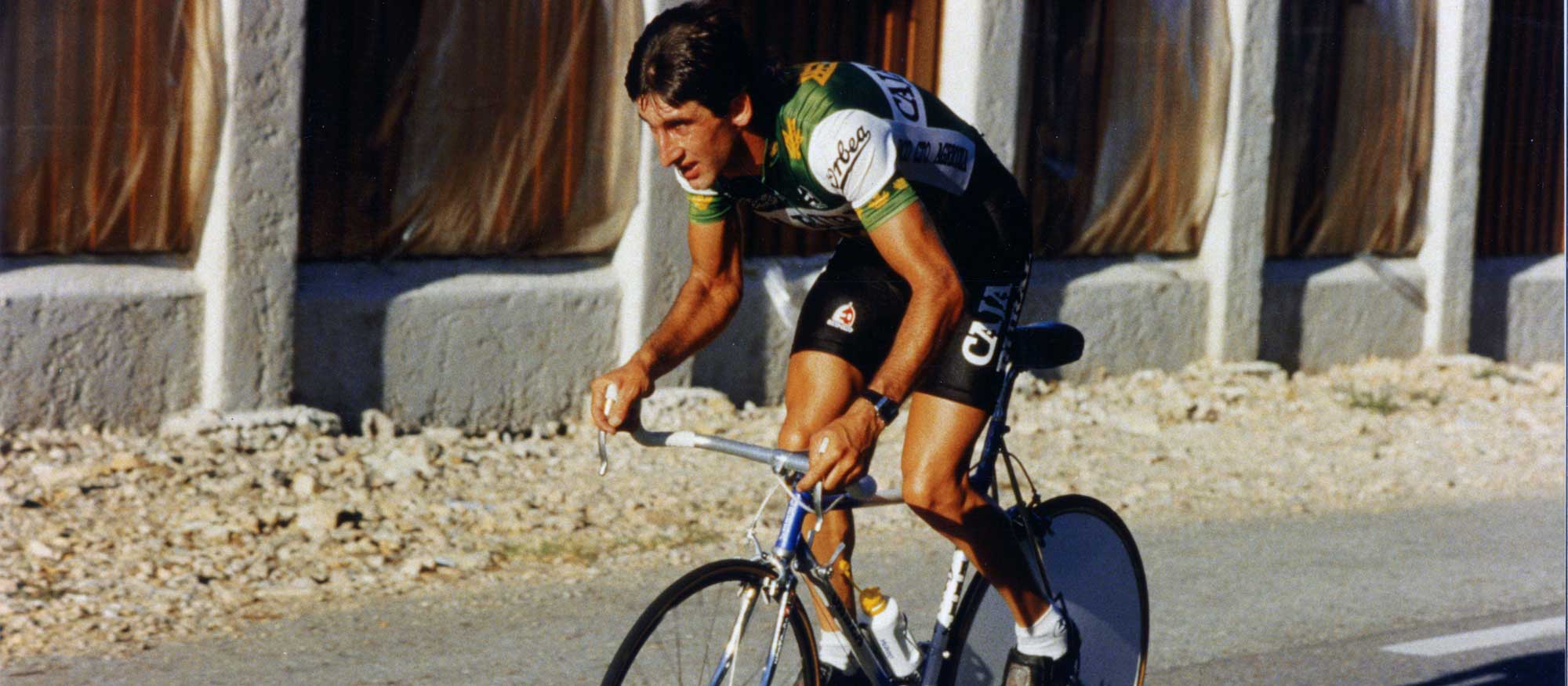

A chat with Marino Lejarreta (Berriz, 1957) is a chat with a cycling icon in our country. Going by the nickname “The Reed from Bérriz,” he thrilled all good fans during his 13 years as a professional (from 1979 to 1992), during which time he competed on various teams, among them the mythical Seat-Orbea, where he arrived following the departure of another legend: ‘Perico’ Delgado.

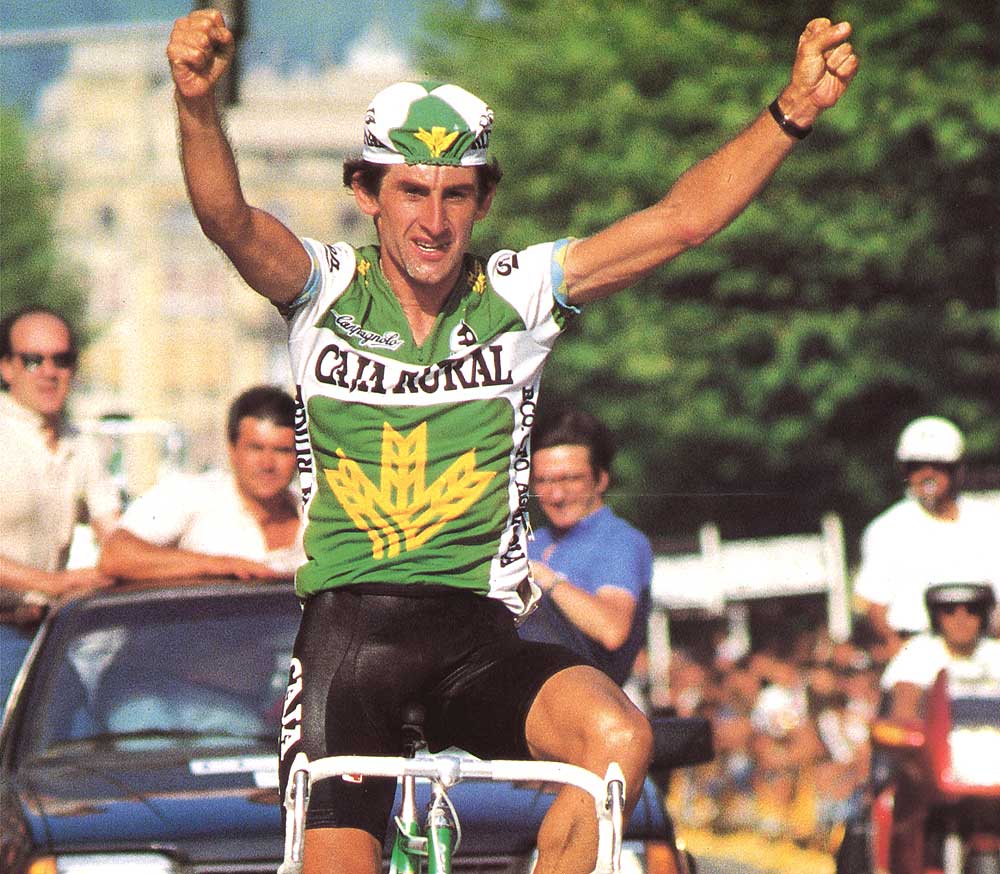

He’s a link in the saga of illustrious cyclists (his brother Ismael was a pro until 1983, and his nephew, , whom we’ll always remember with love and affection, Iñaki Lejarreta, competed with the Orbea Racing Team). His honors include 52 victories, among them the ’82 Vuelta a España; two stages in the Giro de Italia, and in particular, a stage in the Tour de France of 1990, where he beat out Miguel Induráin at Millau, in the same year that the Navarrese rider’s career took off.

Lejarreta was a “daring climber” whose passion pushed him to fearlessly tackle the mountain. That same passion for bicycles remains intact, as you can see in this interview that he gave us a few weeks ago, taking advantage of his visit to our facilities in Mallabia.

Many say that your style of riding makes it seem like you were born to be a cyclist. How did you discover your passion for cycling?

One thing is passion and another competition. Passion is something I think I have had since I was born. Before, it was a great privilege to have a bicycle, and my father had one to go to work, although in the end, the whole family used it. Over the years, we started to have different bikes: my brothers were the next ones to get one. We used it to go to different places and we spent the entire day on the bike with a sandwich: Gorbea, Aizkorri…They started to compete and following in their footsteps, I also got started in competition. That’s how I came to be a professional. It’s a passion that has not disappeared, even though I’m retired.

How old were you when you got your first bike?

The first bike of my “own” – before we shared it among all us kids – I got it when I started to compete when I was 16 years old… although it was second-hand and made up of parts we had to buy separately. It didn't even have a brand name (he laughs) … I remember that the first bike that appeared at our house, though, my brother’s bike, was an Orbea. We got it thanks to a neighbor who worked there.

During your career, you’ve achieved great things: stage victories in all three Grand Tours, an overall victory in the Vuelta, three victories in the San Sebastián Classic… How do you remember ‘Marino Lejarreta, competition cyclist’?

I think I was a daring climber, because I rode more from the heart than from the head. When I got that impulse to ‘go for it’ it was because I felt like it, without thinking too much about the consequences, and sometimes it backfired and sometimes it turned out well. It was my way of racing and I enjoyed it like that.

It was an era in which team strategies were less important than the sensations of the cyclist; it was a more aggressive and impulsive cycling, wasn’t it?

Yes, there were also strategies, but in my case, it worked based on impulse. Many times my body told me to attack at the start of the pass, and I did it without thinking that I could wear out halfway up the climb. Logically, over time and with experience, these aspects have been refined and now the evolution of cycling, with aerodynamics and the materials have made everything faster: now it is more difficult to ‘break up’ a race, even on the climbs.

|

|

|

|

You also heard a lot of talk in the 80s and early 90s that cycling was a sport for sufferers; for ‘miners’. Today, cycling is associated with leisure, with fun, with outings with friends, routes… Do you have that same impression?

It was like that back then, too. What we have to do is differentiate competitive cycling from leisure. Although today, in many cases, bicycle touring is also associated with competition, because many bike tourists want to compete; it demands a certain level, a goal… In this sense, we have to accept that it is a sport with a certain bit of agony associated with it, because the effort is primarily on an individual level; there are many kilometers, tough ramps, etc.

Of the 52 victories in your professional career, the ones you won by following your heart, which do you remember the most fondly?

I have a lot of them in mind… From the Vuelta a España in 83, for example, where I came in second in the overall, I have a better memory than in the Vuelta of ‘82, where I won in the Overall (after the disqualification of Ángel Arroyo). I also have fond memories of the Los Lagos stage of that year. The start was in Aguilar de Campoo, where it was terribly cold, to the point I thought about quitting…. Later, the weather changed and during the climb, I had no intention of attacking, but I looked back and I found myself climbing alone. Then I thought:“Something is happening here; it can't be that I’m riding that hard.”I was cool-headed enough to wait until the toughest part was past, the La Huesera section, and from there I gave it all I had until the finish line. It was an unexpected victory and a very nice one for me.

In the end, that 2nd place in the ‘83 Vuelta was more gratifying and you ended up feeling more satisfied with your performance than in ‘82, when you were the winner…

Yes, I have a similar feeling about the ‘91 Vuelta, in which I was third and Melchor Mauri was champion. I think I did a good job achieving that result. There were also other races, like the Vuelta a Burgos or the Vuelta a Cataluña, where I didn't expect a victory. Strangely enough, I won the first Vuelta a Cataluña (1980) thanks to the good time trial I did, which took the Dutch riders of TI-Raleigh by surprise. That's the thing about cycling: sometimes you have great expectations and don’t achieve anything, and other times you don’t expect it and win.

When did you realize that your professional career could be as long and successful as it finally was?

The first year, in ‘79, I couldn’t do a lot, because I had to do my military service and I trained very little on the bike. I started off really bad at the Vuelta a España, because I lacked experience, but I ended up great… If I would have had another week, who knows? I had the points to indicate that it might continue. The following year, with Teka and doing things right, the first victories rolled in: Vuelta a Asturias, Vuelta a Cataluña, Montjuic… Which confirmed these expectations.

There is a video of your stage victory in the Tour de France in which you don’t raise your hands to celebrate it; some take this as a sign of the humility that has characterized you as a cyclist…

Well, the truth is that I didn't celebrate it because I didn't want to look ridiculous (he laughs) … Like when you see some cyclists raise their hands and then it turns out that others have won. That day there had been a breakaway of around 20 cyclists ahead of me and in the confusion of the race, I wasn’t sure if I had passed them all… I didn’t celebrate it out of a sense of caution (he laughs).

Of the three Grand Tours, you’ve always been especially fond of the Giro. Why is that?

The races are completely different from one another in terms of their approach and philosophy. The Tour is the most important and commercially, the one that moves the most resources. La Vuelta has had its ups and downs over the years and has its bit of nostalgia, but neither of them has the soul that the Giro has: the fans are passionate, die-hard cycling fans and they worship the riders. In the Tour, for example, there are a lot of people who invade the course and people who want to receive more attention than the riders. It’s not just something I say, many professional cyclists have the same idea.

That Italian passion for cycling…do you think it’s comparable to what we have here in the Basque Country?

It’s possible. The Italian version is perhaps more effusive and visceral. Basque fans are very knowledgeable about this sport in general: they go to see the race, not just a particular rider or team. They appreciate all the cyclists and their effort just the same.

What differences do you see between cycling in your day and now?

Most of all, the speed. But also the material: we’re talking about bicycles that weigh more than 9 kilos and now I think the limit is at 6-7 kg.; better developments, next-generation materials, aerodynamics, etc. There’s also the preparation and diet of the cyclists. Although in essence, it’s still the same cycling, there is a difference in terms of strategies and monitoring technologies; you can no longer do the crazy things we did before, because they’re watching you down to the last millimeter.

Nowadays there are also specific bicycles that are lighter for climbers, or ‘Aero’ bikes designed for racers… Do you ever talk about this evolution with riders from your generation?

Even though before we all rode the same bike, to put it that way, I think today the peloton is more equal. Nowadays most riders have the opportunity to train the same way as the best riders do, to have the same information and the same material. Before these “social” differences were greater: the “worst rider was worse” and the “best rider was better,” because they had more resources and assistance.

What technological evolutions have surprised you the most?

In particular, the weight reduction and the improved performance and rigidity of the frames. We also need to keep in mind that the roads are in better condition…

What cyclist surprised you the most back when you competed? And now?

Hinault. He was off the charts: he could go at 70% and you at 100% and you still couldn't catch up with him. He was from another galaxy. With regards to the riders today… Once you’ve been a professional, you tend to demystify many riders and you no longer mystify others. It is difficult to appreciate a professional rider in the same way once you’ve been one. Maybe for the closer relationship, with Contador or Purito.

What is the strangest or most curious thing that has happened to you while competing or training?

The occasional confusion about the road… Something similar happened to my brother in an amateur race: one time he crossed the finish line backwards and they kicked him out of the race for not following the correct route (he laughs).I also took a 5 km detour in a race like that. In professional races, I have a few stories like that, especially with snow and fog. I remember a Paris-Nice (82), coming down from a mountain pass and the road was completely white. With the bike, we got down fine, leaning on one foot: the motorcycles had a more difficult time.

People still stop you on the street to talk about different aspects of your career. What do they say?

People remember you fondly and many tell me that I instilled in them a passion for cycling. I’m proud to receive praise like that. Some tell me that I still look like I’m in good shape and could still lead the peloton (he laughs), but I’m no longer up for that. I’m still involved with bikes, I also usually do a couple of hours of MTB with a group of friends, but on a different level and only when there’s good weather (he laughs).

What was the mountain pass that made you suffer the most? And which did you enjoy the most?

I had a terrible time in the climb at La Marmolada, because I knew I didn't have a chance and I was exhausted. And where I had the best time… In many of them, really. If I had to choose, I’d say at Los Lagos.

This year we have two Basque teams in the peloton: Murias and Euskadi, both riding Orbea bikes. What do you think about these projects and the popularity of cycling in the Basque Country?

They are projects that come to light after a time in the shadows following the end of Euskaltel-Euskadi, a very beloved team, recognized by the fans and riders around the world, and whose disappearance was a tough blow. Now we’re coming out of the hole, that’s why we need to work harder than ever to get back the dream. The Basque Country has the material for elite teams, but we have to join together and row in the same direction to move it forward.

Since your retirement from cycling, you’ve been linked to it by managing teams, commenting on races. Where are you at now?

I try to go out on the bike in the mornings on the days I can and when everyday tasks let me.

Do you know about the sports tracking applications? What do you think about them?

I use one sometimes, but it doesn’t do much for me in terms of sports. It is good for personal monitoring and to see your progress, as information, but I’m not obsessed about it. Even though technology is also my passion… In fact, I did a Master’s degree in industrial electronics and I was always the one who played around with the transmitters, walkie-talkies, earpieces and the rest of the electronic gadgets when I was on the ONCE team.

I’m also very interested in the technological advances made in bicycle mechanics. When the electronic changes came about, I knew that they were going to be the future.

Finally, why do they call you “The Reed of Berriz”?

A journalist made it up: Benito Urraburu, who wrote for the Diario Vasco. I suppose that it occurred to him because of my height, thinness and because he thought I was a tough cyclist. But only he knows…