16 May, 2019

The art of competition tells a story

When we talk about the art of competition, we aren’t talking about victory. It goes much deeper than that.

Victory might attract the attention of cameras and bring your name to the spotlight, but for us, competition is where our demands to be the best—and work with the best—pay off. And these demands has driven us to improve what we do since 1931.

Competition as our DNA

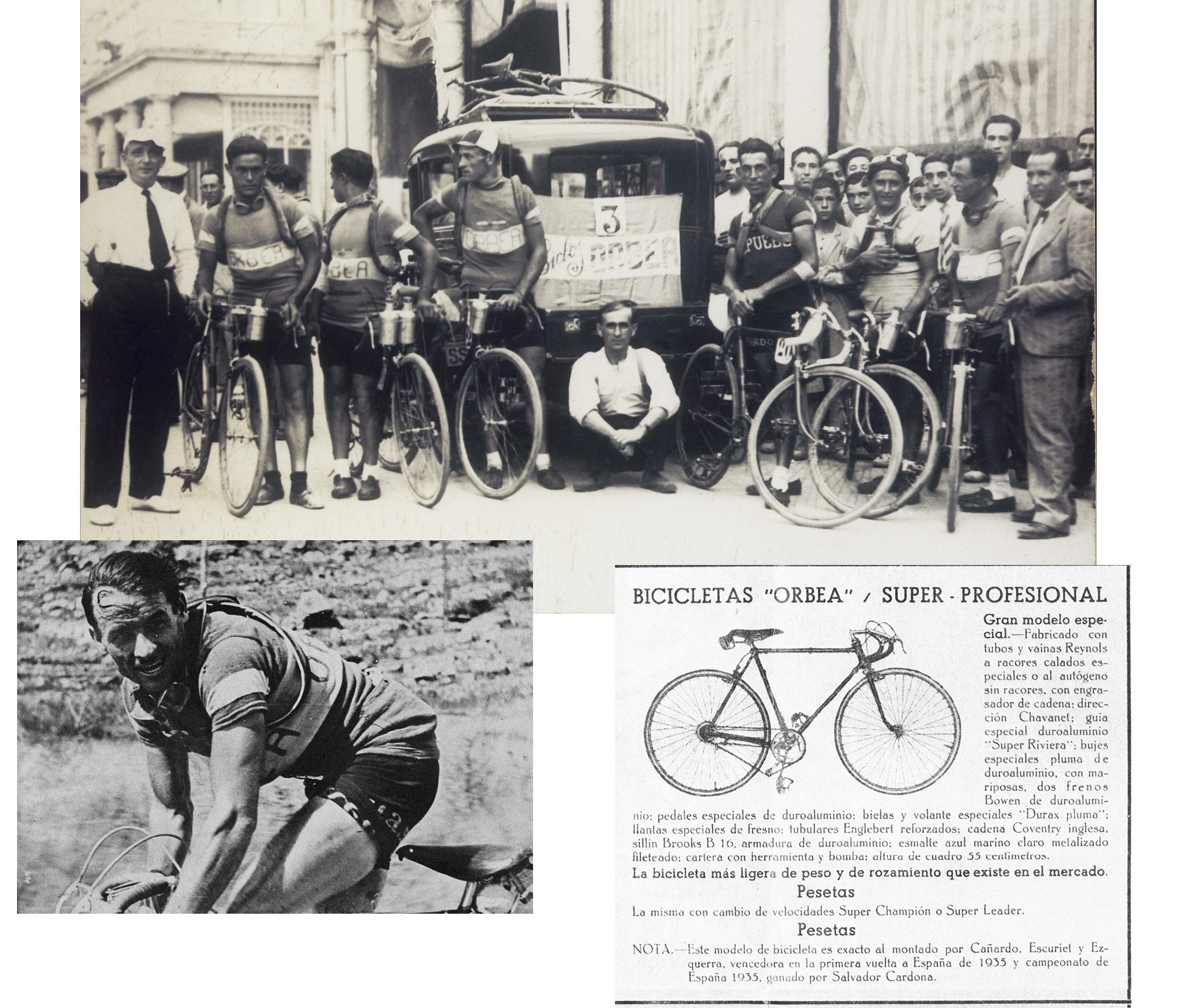

The 1930s mark the beginning of our bike manufacturing history. Our first line of bikes included three models, one of which was built for competition. This race bike had all the high-level details: a steel frame, mudguards, no gears and top-of-the-line finishes like anti-rust coating and waterproof pedals. The year was 1931.

Our first line of bikes

Mariano Cañardo was the Champion of Spain and a true idol for cycling fans at the time. In 1935, two things would change cycling forever: the birth of Vuelta a España (Tour of Spain) and cycling’s first gearing system.

Fifty riders lined the peloton in the first Vuelta a España. Among the pack, Mariano Cañardo held down second place on his Orbea Super Professional, our steel racing bike which also included aluminum in some of its components—a novel material that was used to improve the rigidity of the bike.

The gearing system consisted of a wheel with a pinion on each side. To change gears, the wheel first had to be removed and rotated. A year after the start of Vuelta a España, Federico Ezquerra claimed our first victory in the Tour de France.

One of our first athletes, Mariano Cañardo, in action and riding Orbea’s first competition-level bike

Not long after his victory, the Spanish Civil War broke out and, shortly thereafter, World War Two: events that forced the entire bike industry to stop its manufacturing and competitions.

The evolution and sophistication of materials

After both wars ended in the 1940s, competitions such as the Tour de France and La Vuelta a España resumed, and the industry regained its strength. Bikes like our Orbea Carrera Professional were suddenly equipped with a rear derailleur as we know it today.

The Carrera Professional was a bike created from the “indications of the champions.” The quality was evident in components such as the bottom bracket or the extra-thin cranks, as well as other improvements that shaved weight from the bike. This was noticeable in races: the average speed increased gradually in all the races.

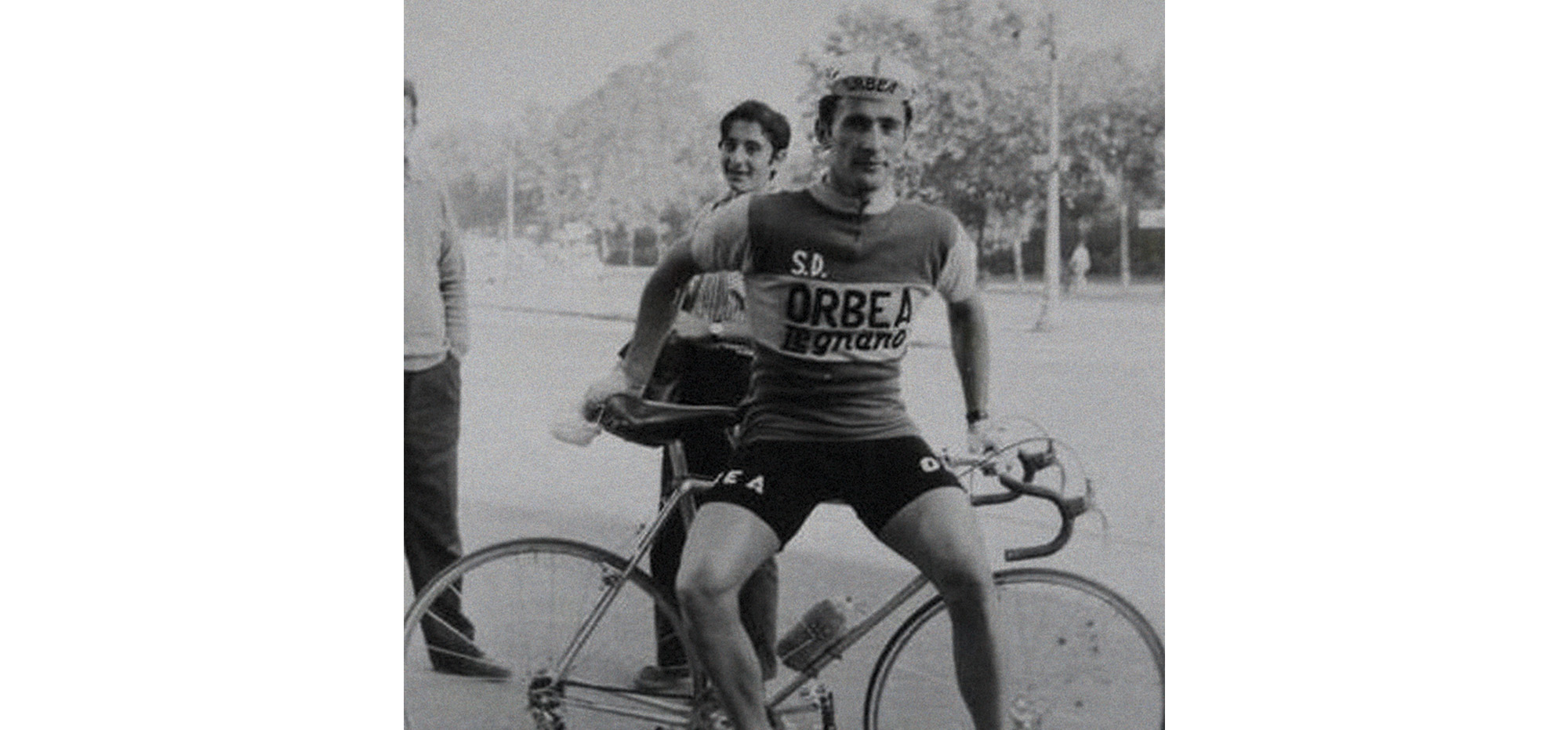

Cycling team during the 1940s

Competition bike in the 40s: wooden wheels and rear derailleurs

From this time until the 70s, our legacy in competitive racing focused on individual sponsorships, although in the 60s our catalog had expanded to three competition-level bikes. The so-called “great competition,” our competitive flagship bike, was double plated and included components manufactured by us, with the exception of tires.

It was in the 70s when our competitive pulse returned and we resumed our involvement in racing by debuting a new team. We focused on the rake of our racing bikes, which dramatically improved the effectiveness of pedaling, and continued using steel as our main material (although one type of aluminum, duraluminium, was used in some components).

One of the cyclists during our return to competition in the 70s

Competition-level, double-plated model in the 1970s

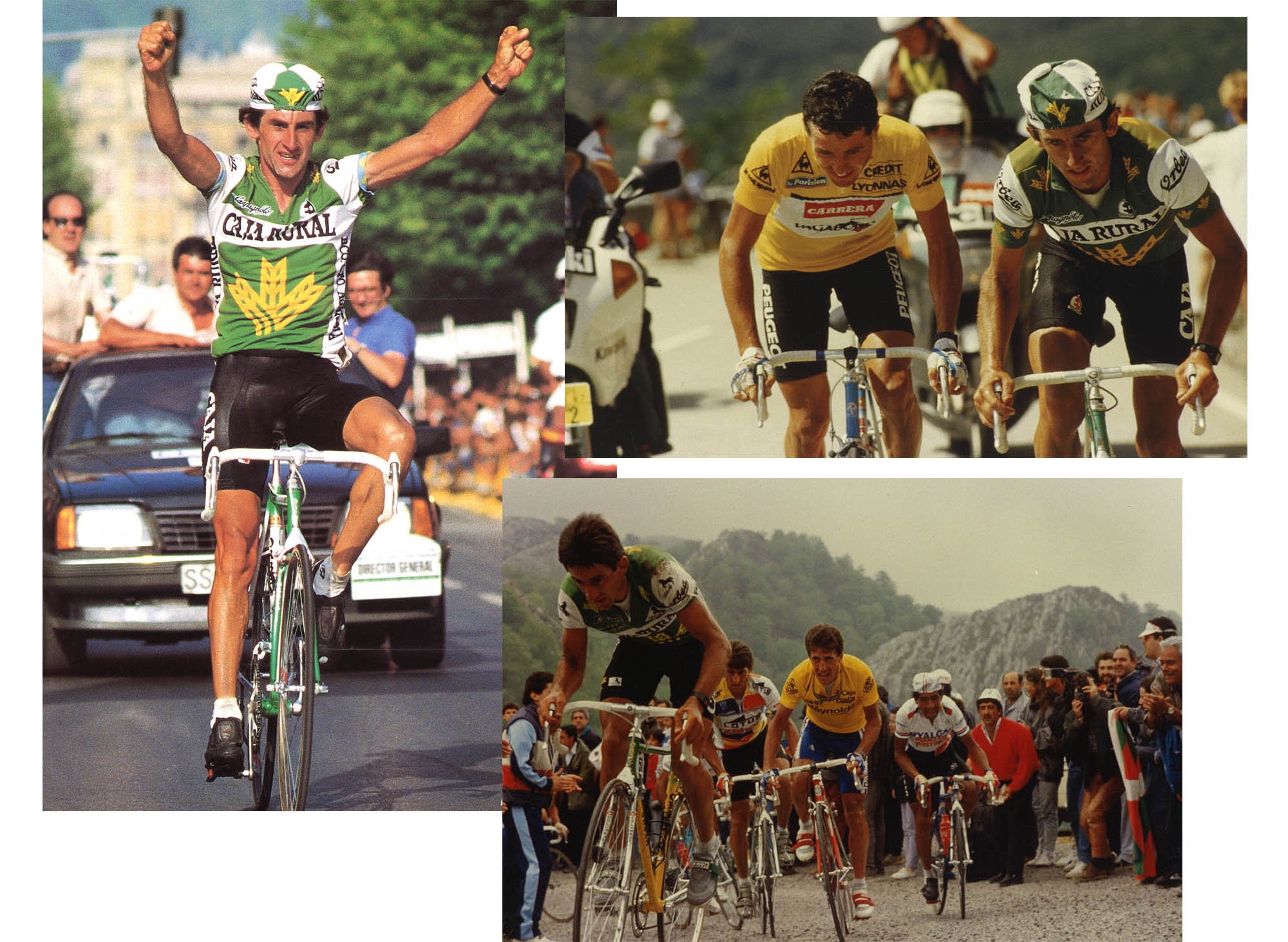

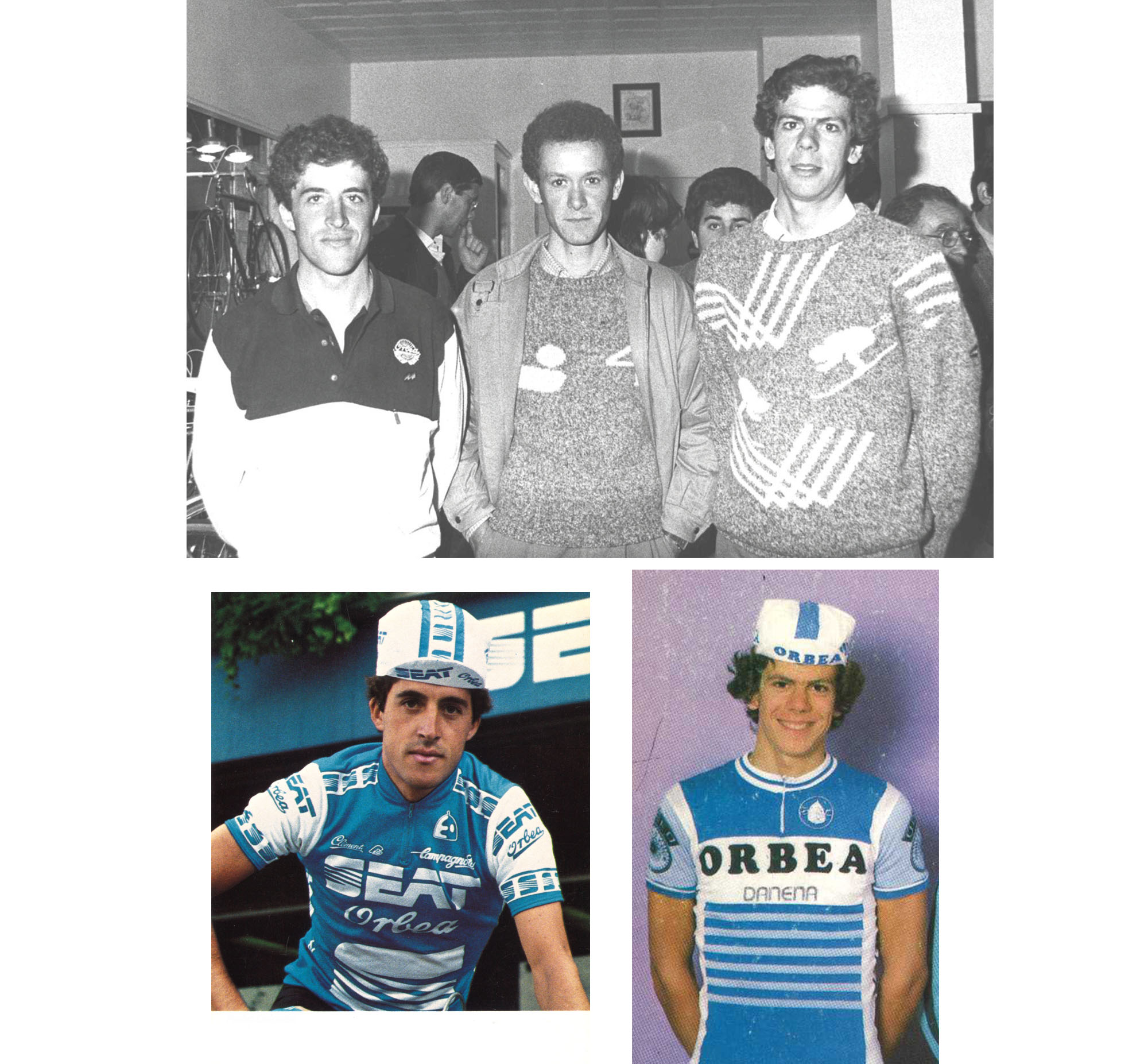

The 1980s was a powerful decade and probably the most significant in our history. After our first professional road team, names like Peio Ruiz de Cabestany, Pedro Delgado and Marino Lejarreta arrived and began claiming victories in the three big road races (Tour de France, Vuelta a España and Giro d’Italia). In fact, Pedro Delgado took the Vuelta a España in 1985, the same year that our women's team debuted—one of the first women’s team in Spain.

Marino Lejarreta in action

Pedro “Perico” Delgado (left), Peio Ruiz Cabestany (right)

Peio Ruiz Cabestany’s team bike in the 80s

First women’s cycling team

The material, for its part, continued to evolve and began to rival prestigious Italian cycling brands.

In the 1980s, the eruption of mountain biking took over a large part of the competitive spotlight, as well as the attention of product developers. Until 1994.

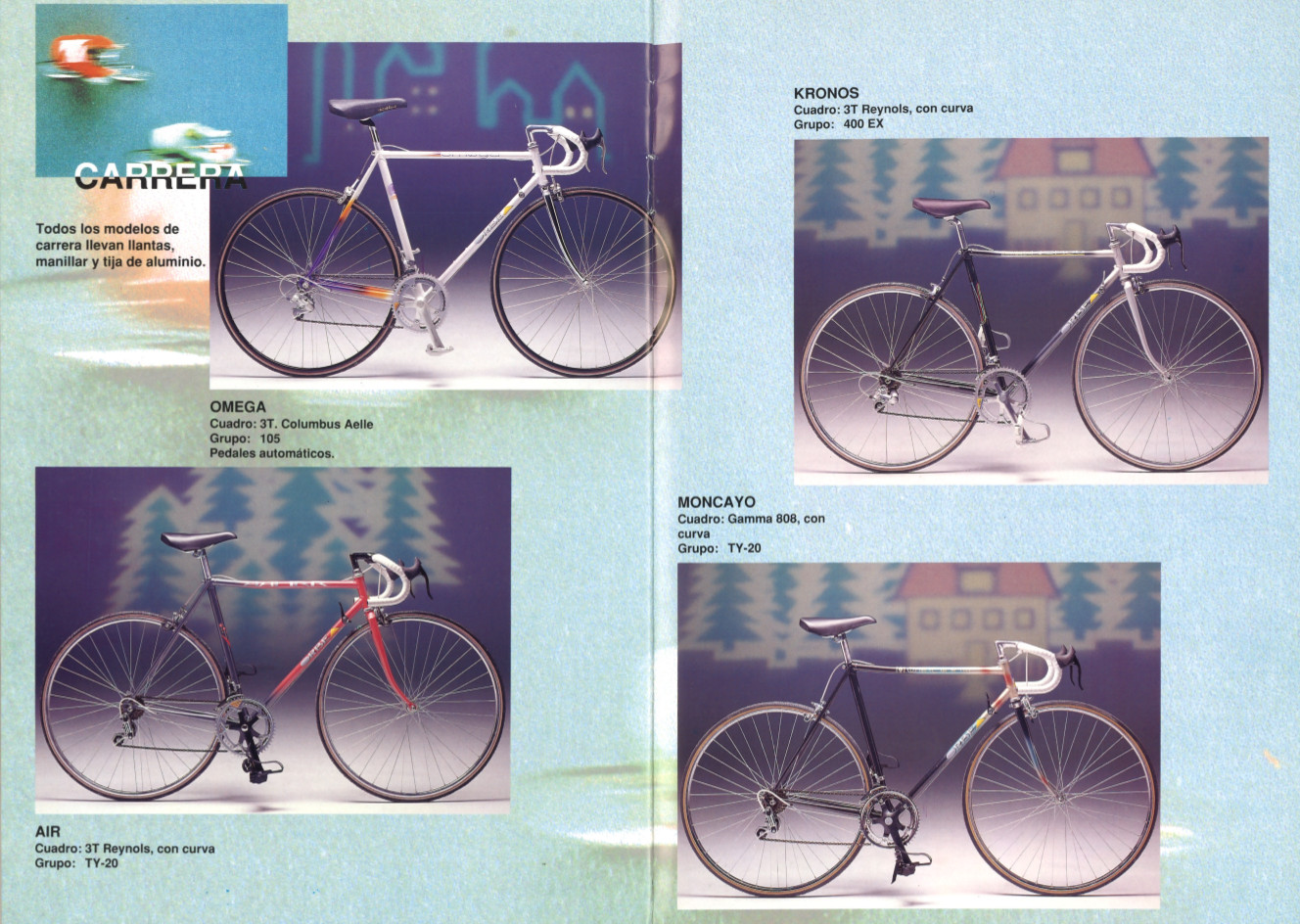

Competition-level bicycles in 1993, just before the creation of the Euskadi Foundation

That year, the Euskadi Foundation debuted and steel-frame bikes came to an end: it was the last year that a steel bike won a race like the Tour de France. Aluminum entered the scene, but only for a short time because the carbon fiber revolution would be coming.