3 October, 2014

CHEERING FROM THE ROADSIDE

It all begins in a bottomless trunk: the eyes, the only place where you can keep everything.

When she opened her eyes, Regina had them filled with bikes. The eyes of Regina – her mother gave her that name so that they’d always remember the grandmother in her – and the eyes of her older brothers, Markel and Oinatz. Through the endless tunnel of their eyes, they soak up everything. Children are like this. They’re sponges. They keep everything they see. And everything they hear. At home, Markel, Oinatz and Regina can hear people talk about cycling just as they talked about the weather – that is, all the time. Bicycles are just one more home appliance. They’re more common than brooms and more useful than a water heater. Regina is always on her bike. The bike is as familiar asher favourite teddy bear – a trusted friend. They first met when the girl was two. Now, being four and riding without stabilizers, she climbs all the way down from Gatika to Mungia (5km) with her parents to the baker’s. She also rides to school with her brothers every day, complaining that the cold air on wintry days hits her hands and face. But her complaints vanish into thin air. She has to pedal her way to school. Her mother, Joane – the great Basque cyclist Joane Somarriba, winner of a World Championship, three Tours de France, two Girosd’Italia, and many other races – feels tempted to tell her what you feel up there in the mountains, in the Pyrenees or the Alps. She wants to show her daughter how that resembles happiness, or at least how it made her and her husband, Ramontxu González Arrieta, happy. Ramón is a cyclist too, winner of the Classique des Alpes and teammate of Indurain in his golden age in the early 1990s. But she doesn’t say anything. She wants Regina to discover it herself, and so Regina’s eyes get filled with bikes.

‘Just like mine,’ Joane says,picturing a girl standing by the road from Bermeo to Sollube in the Vuelta a España in the 1970s. The girl is her. Her father had taken her there to see the riders. He was a sailor, spending long months at sea. When he came home, it was as if a mighty wave pushed the door open and every room got flooded with the two-wheel spirit. ‘Dad loved cycling and he passed his passion onto us. Everyone talked about cycling at home; my childhood memories include a lot of cycling images.’‘May was the month of the Vuelta a España. In the ikastola (Basque school), we rode our bikes the way Eddy Merckx, Marino Lejarreta or Bernard Hinault did. It was a big challenge,’Joane recalls. It was the age of adventure, so she got on a small motorbike with her sister to follow the Tour of the Basque Country, only to come back home in the rain, soaked to the bone. And then they had to listen to their angry mother and face the music: ‘To your room, now.’ But they were so happy… They’d go to bed and dream of bikes and riders.

‘This was so common in Euskadi… The cycling tradition was so strong that it was transmitted from one generation to the next, as if wired into our DNA. Our passion for cycling had a lot to do with watching and listening to our elders. We inherited the passion and also the admiration for cyclists: the sacrifice they made, the time they spent on such a tough sport…’

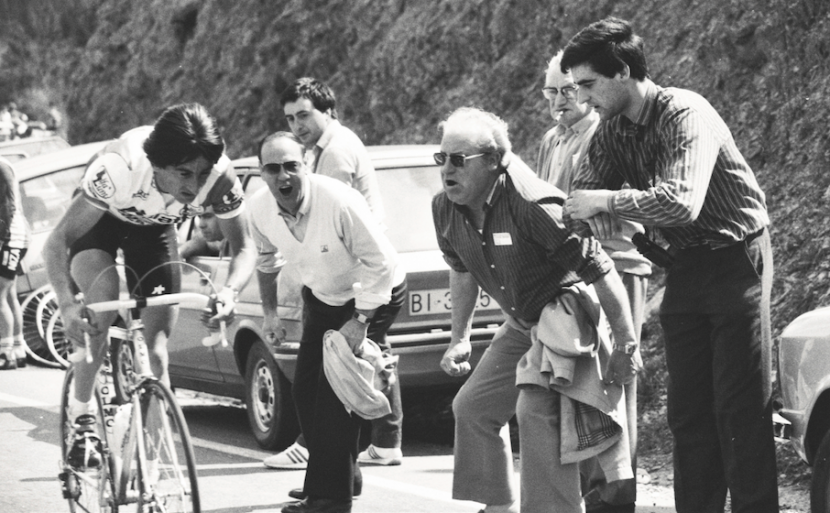

This admiration and the associated toughness Joane could experience herself, for cycling fans just loved her. ‘I can still remember how the Col du Tourmalet was packed with people, people from home, and how I had no strength left but I hanged on because of them. They encouraged me to keep going.’ This is a common picture among cyclists: An empty roadside gets you down, while one filled with eager eyes boosts your adrenaline. This is what Somarriba felt in the Tour de France 2001, whose starting point was Bilbao. ‘It was unforgettable, something larger than life.’ The roads were lined with fans. ‘I’d never seen so many people in a women’s race, and I never saw them afterwards. And it wasn’t just me. Every rider was amazed. They couldn’t believe the atmosphere, the crowds cheering each and every rider on, not only me (Joane was their hero, of course, defending the French Tour title with the start line at home).’

CUSTOMS AND TRADITIONS

The father of Antón Barrutia (Iurreta, 1933) would have none of it: ‘With one good-for-nothing in the family, we have enough,’ he said, when the boy told him he wanted to be a cyclist like his brother Cosme. Antón was 16. He was working at the stone quarry, making 2,500 pesetas – twice as much as his father. ‘Cycling means pain, suffering, hunger,’ the man warned. But Antón wouldn’t listen. Passion doesn’t listen to common sense.’‘And if there was someone to blame, it was him. He was always talking about races, about Fede Ezquerra, Cipriano Aguirrezabal, Martín Mancisidor… And then there was my brother, too, who was already riding a bike. My father instilled the passion in me; my brother paved the way.’ In the 1930s (the years of the Spanish Civil War) and then after the war, in the 1940s, you could only listen to the races. ‘We used to gather round the only radio we had in town to hear the news from the Vuelta a España. We clenched our fists and got closer when the riders were approaching the finish line. We pictured them in our minds. We thought of them not as heroes, but as noble men, training hard in hot or cold weather, fighting against the elements.’ Antón worked at the stone quarry in the morning, carrying bricks. In the afternoon, he got on his bike and went to watch the Gran PruebaEibarresa or the Subida a Arrate. ‘There were lots of people, many more than now. And they went on foot, with their sandwiches and their bottles of wine. There used to be no other means to get there. But there were so many cycling fans… Why? Because the riders were really good. We had Ezquerra, Dalmacio Langarica and many others. We’ve always had great riders. That’s what drew so many people. There were lots of races, too: Vuelta a España, Gran PruebaEibarresa, Subida a Arrate, Gran PremioOndarroa. I remember that many riders who weren’t Basque – Mascaró, Company, Poblet, Serra, Masip – couldn’t believe their eyes. The people loved us locals, but they cheered everybody on.’ It went on until the rivalry between JesúsLoroño and Federico Martín Bahamontes – a milestone in Spanish cycling. ‘They split the fans,’ Barrutia recalls. It was the rivalry between a rider who was ‘sort of nuts’and a hard-working fellow like Loroño, who caught his opponent’s wheel and kept telling himself, ‘You won’t break away from me, you won’t break away from me.’ They aroused love and hate beyond the sports sphere. When Langarica, who was the coach of the Spanish national team, chose the members of the Tour de France squad in 1959 and left Loroño out to have Bahamontes as single leader, they broke the windows of his bike store in Bilbao and called his wife names on the streets.

‘But they were always kind to me in the Basque Country,’ Bahamontes recalls, grateful. ‘There were so many fans and they were so enthusiastic. They were famous even before you met them. Races like the Subida a Arrate drew so many cycling fans. You just can’t imagine. They came from Eibar, from San Sebastián from Bilbao…they liked me. One year I wasn’t taking part in the Subida a Arrate because I was ill, so the late JuanitoTxoko (the heart and soul of cycling in Eibar) called me and asked me to come. He said I drew lots of people.’‘People have always loved a good show,’ Barrutia adds, ‘and Bahamontes, like many others with him, knew how to put up one. People appreciated that. And so they lined the roads.’

‘Let’s go race in the Basque Country,’ said the Moliner team coach once to Pedro Delgado (Segovia, 1960), then a junior rider. They came and went back home without racing, angry and tired. ‘So my first impression was a negative one. I came back home thinking, “What with Basque people! Who do they think they are? Not letting us race…”,’says the rider from Segovia, whose child’s eyes are filled with bikes and landscapes from Castile, with parched, empty fields reaching into the horizon. ‘We used to race alone here, for occasional onlookers who just happened to pass by,’ he recalls. ‘They say the best fans in Spain are in the Basque Country. And they’re right. I learned this the second time I went there, because then I was able to enter the race. Being used to riding for no-one, the crowds on the roadside struck me. They were everywhere: by the road, in mountain passes, at the start and finish lines… I’d never seen something like that before. And then I learned it was always like this. No matter the race, no matter the category, the crowds were always there. And they weren’t just any crowd: they were a qualified, critical audience. They knew about cycling, they understood the rules, they were familiar with the riders (all of them: juniors and veterans, even those who were still in their teens), and they had well-informed opinions. When they spoke, you knew they were valid interlocutors, even when they were criticizing you. You knew you could have an interesting conversation about cycling with them,’ Delgado says. Like Bahamontes with Loroño, he shared the setting (both the mountains and the decade, the 1980s) with Marino Lejarreta, the rider who was greater than his record sheet.

Fans just loved him. ‘People liked a show,’ Delgado explains. And Marino knew how to give them that. He was an astonishing cyclist, winning followers – or should I say devotees? – over as he lost races. He rode his heart out. He let his soul speak, express itself, feel free to attack – and lose. His defeats felt like victories. Standing on the podium, mostly on the second place step, the ovations were always for him. ‘But they also thanked us, his rivals, appreciating it if we were able to put on a good show. I’ve always felt they liked me in the Basque Country. And riders like Vicente Belda, who were ready to die on the bike too. That’s what they wanted,’ Delgado insists.

Marino made huge efforts on the bike, but he was also close to the people, an ordinary guy, flesh and blood you could touch, someone you could talk to if you came across him on the street. He embodied everything that Basque fans loved. Jean-Marie Leblanc, General Director of the Tour de France from 1989 to 2005, says Basque people like cycling because this sport stands for the values they cherish: courage, determination, boldness, dignity… This is what cyclists mean to Basque fans, irrespective of the jersey they’re wearing, the name they have or the colors of the flag they defend. This is what they admire in their favorite riders. In a thank-you note to his Basque fans, German pro Jens Voigt praises their loyal support: ‘They’re always there, in rain, shine or snow, always ready to cheer you on when you’re in pain. They’re encouraging to both the leaders and the last riders in the field.’

This is probably what Roberto Laiseka felt too when he won a Tour de France stage in Luz Ardiden, back in 2001. ‘I can’t remember many stages where suspense and symbols were so powerful,’ says Leblanc. ‘The Pyrenees turned orange, the color that’s become synonymous with Basque cycling – a social phenomenon to be found nowhere else in the world.’ In the words of Delgado, ‘It was a powerful idea, identifying Basque fans wherever they went. But a word of caution is in order: the huge tide of Basque cycling fans didn’t emerge when they got dressed in orange. They existed way before that. In fact, they’ve always been there.’ Right from the cradle.

Some people say that Spanish cycling was born in the Basque Country. That the Vuelta a España has its origin there. Some of the best, legendary teams certainly do: Kas, Fagor, and others. And boys and girls from the Mediterranean and from the Castilian plateaus traveled north to become cyclists, in a sort of forced migration to their two-wheel university. That was the path Delgado followed. And many others like him: PacoMancebo, Carlos Sastre, Joaquim Rodríguez, Alberto Contador… All of them. Or almost all of them.

Paulino isn’t a rider. He’s just a pensioner who spends his days under the sun of Castile, his homeland. In the 1950s, the dark years after the war, he migrated to Euskadi – not to become a cyclist but to find a job. And he did find one, in a manufacturing plant in Mondragón. Being there, he stayed for the show: the Subida a Arrate, the roadside packed with people. A superb picture. According to Antón Barrutia, the passion is weaker now. It’s not the same. According to Pedro Delgado, audience shares soar in the Basque Country when they broadcast a race on TV. Paulino is neither here nor there. He remembers Bahamontes and Loroño, of course. He grins when he thinks of Juan José Sagarduy and his slipstreaming. He says he’s seen it himself, that nobody told him about it. Meanwhile, Regina rides down with her parents to get her family’s bread in Mungia, and her eyes are filled with bikes.